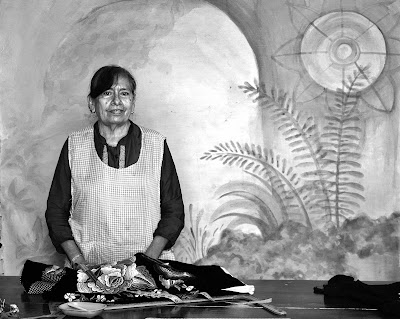

Her business was thriving until the revaluation of the peso in 1997. The financial crisis hit her hard. People opted to buy clothes at department stores rather than have their clothing handmade. Her classes also dropped off considerably. Young people were turning to online courses rather than in-person classes. It was a difficult period, but she managed to survive. What allowed her to survive was her ability to embroider typical indigenous designs and to transform older traditional garments into dresses for weddings, quince años, and evening gowns. She has learned to embroider the designs from the Istmo, Mixe, la Costa, el Valle Central and la Mixteca. She also designs outfits for the major fiestas of these various indigenous regions. This is very laborious and detailed work that takes much time and expertise. But because it is such an important part of the culture, people are willing to pay the price for a job well done. Liz is proud of the work she does. "No es justo una costura; es un arte" (it isn't just sewing; it is an art).

What Liz likes best about her job is the satisfaction she gets from cutting a piece of fabric and creating a garment that pleases her clients. She studied with a tailor and learned how to make the very precise measurements needed for a perfect fit. It shows in her work, it is an art form, not just a trade.

At age sixty-five, Liz has no plans on retiring. She loves the work that she does and wants to pass it on to the younger generation. She often works seventy-two hours a week and enjoys every minute of it. "As a seamstress/dressmaker, you never stop learning. New fashions come and go, people's bodies change size and shape, and we must change with them." As I was about to leave, she brought out a file of diplomas and recognitions that she had received during her life as as a seamstress/dressmaker. "When I am no longer able to do my work, there is no one to take over my shop. It makes me happy to know that those who I have taught will keep my oficio alive." In preserving her oficio, she is also helping preserve the rich indigenous traditions that make up the cultural fabric of Oaxaca.