|

| Three Muxe Beauties |

I write this post on Thanksgiving day, 2022. I have many things to be thankful for: family, friends, and good health among them. But I want to add a word of thanks that events like la Vela de las Aútenticas Intépidas Buscadoras de Peligro (a transgender-gay celebration) can take place in Mexico without violence or bloodshed. This event began the day after the horrible mass shooting at a LGBT bar in Colorado. There were well over 1000 people present dancing, drinking and having a good time. There were straight people, gays and trans people all intermingling and respecting each other. That is not to say that there is no discrimination. Mexico is not free of discrimination and hate. A few days earlier one of the Muxes (third gender) organizers of the event was assaulted. But the event went on without further incident. This year's Queen of the Muxes, Melisa Mijanos Boijseauneau, is a lawyer and became the first transgender official of the government of Oaxaca. In an interview with the press, she commented that for her, being crowned queen represents the resistance of a community that struggles every day against discrimination, violence and hate crimes, a community that resists to show the world its joy for the freedom to love and to be free. There is a lesson to be learned here and I feel privileged to have been present and accepted by everyone there.

|

| Reina Melisa 2022 |

Although the event is "a show" that is only a small part of the Muxes culture, it is still a sight to behold. The imagination and color that fill the venue are captivating. The runway for the coronation of the Queen was a five star performance and after two years of not having the Vela because of the pandemic, people were hungry for the spectacle. (See photos at end of this post)

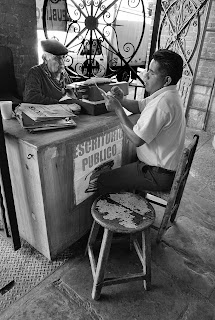

But this trip to Juchitan was much more than la Vela de las Muxes. Two of the people that appear in my book, Somos Oaxaca, live in Juchitan. I was able to present them with a copy of the book they appear in. It was very satisfying for me to fulfil a promise I had made to them and to myself to bring this project to fruition.

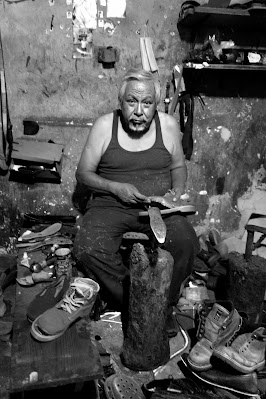

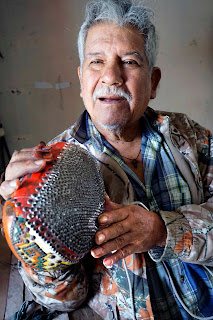

I took a moto taxi to Roberto Sanchez' house without announcing my arrival. Roberto is a tanner and I had not seen him in over five years. He was quite surprised to see me, but was very pleased to receive the book. He told me much had changed since the pandemic and he had to change the location of his tannery, but he was still working. That is what gives his life meaning.

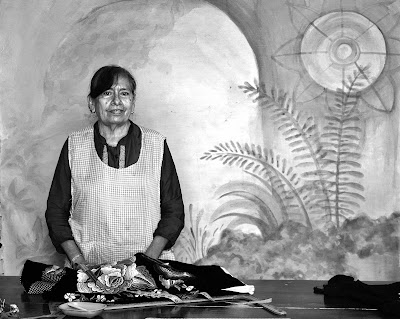

I then went to see Martin Valdez Toledo, a clay artist and and encyclopedia of Zapotec culture, especially in the Istmo region of Oaxaca. Martin specializes in making Tangú Yú, clay statues that represent Zapotec gods and goddesses dating back many generations. I told Martin that I was thinking about a photography project about "los sabios" (wise people) of Juchitan and he offered to help me make contact with them, Many speak only Zapoteco and Martin said he would be my translator. He is a true gold mine of cultural information. I am excited at the prospect of working with him.

Juchitán is a very culturally rich region of Oaxaca. Zapoteco is still widely spoken and the customs and traditions are deeply rooted. I have very good connections with people there who can open doors for me that are not easy to open. Now that my book, Somos Oaxaca, is finished, I would welcome a new project. Juchitan would be an exciting place to begin one. There are still many more lessons to be learned.

|

| Martin Valdez Toledo |

|

| Muxe after church blessing |